- Home

- History of Embroidery

EMBROIDERY THROUGH THE AGES

The History of Embroidery: A Story Told in Thread

From Anglo-Saxon monks to Victorian schoolgirls — how English embroidery shaped the craft we love today.

People have been decorating fabric with needle and thread for centuries. What started as ecclesiastical vestments stitched by monks eventually found its way into homes, onto clothing, and into the hands of ordinary stitchers — people like us.

Here's a walk through the key periods that shaped English embroidery into the craft we practise today.

The Anglo-Saxon Period

The earliest records of English embroidery are ecclesiastical. Around 700 AD, Aldhelm of Sherborne wrote about needlework being a trained skill — no one picked up a needle without proper instruction.

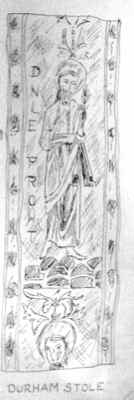

English kings gave richly embroidered robes and vestments to the church, and some of those pieces survived. The Durham Embroideries — a stole and maniple created around 1000 AD in honour of Saint Cuthbert — were discovered in Durham Cathedral centuries later.

They feature the Holy Lamb with Apostle figures, worked in red, blue, green, purple, and gold thread on linen lined with silk.

These are among the oldest surviving examples of English embroidery, and the quality of the work is remarkable for its age.

The Norman Period

This period gave us one of the most famous pieces of needlework in the world: the Bayeux Tapestry.

Despite its name, it's not a tapestry at all — it's hand embroidery. Commissioned by Bishop Odo (half-brother to William the Conqueror) shortly after 1066, it depicts the Norman Conquest in vivid detail across a coarse linen strip 230 feet long and just 19.5 inches deep.

The embroidery uses stem stitch and laid work in wool, with a colour palette of six shades: blue, two greens, buff, red, and grey. The colours were applied freely rather than realistically — you'll spot horses with one blue leg and one red, and figures with green hair.

What makes it extraordinary is the storytelling. The scenes were drawn by hand before stitching, and the skill of those drawings is remarkable. Figures vary in posture and expression across hundreds of scenes, and the narrow borders running along the top and bottom are filled with birds, beasts, rural scenes, and illustrations from Aesop's Fables.

The Golden Age of English Embroidery

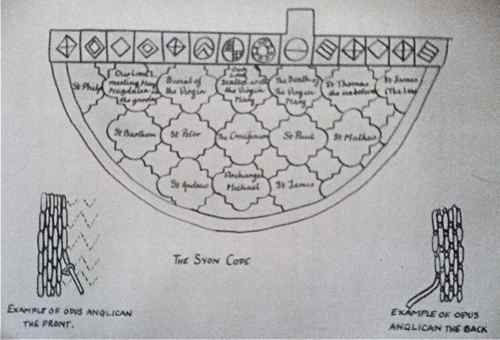

This was the golden age of English embroidery. The standard of work made the country famous across Europe, and the technique that defined the period was Opus Anglicanum — a specialised couching method that produced a surface resembling satin stitch worked in a chevron pattern, using gold and coloured silk threads.

The finest surviving example is the Syon Cope, a ceremonial cloak covered in interlacing quatrefoils outlined in gold and filled with scenes from the life of Christ. The linen ground is entirely hidden by stitching — every inch is covered in gold and coloured silk. It dates from the latter half of the 13th century.

Other notable pieces include the Tree of Jesse Cope (now in the Victoria and Albert Museum) and the Catworth Cushions — five small panels originally part of an orphrey, featuring Apostles and saints worked in gold and silk.

Designs featured birds, lions, leopard heads, and foliage — vine, oak, and ivy were favourites. The figure work has a distinctive character: high foreheads, bearded men with shaven upper lips, and a complete lack of perspective. The drawing may look childish to modern eyes, but the figures carry a sincerity and dignity that still comes through.

The Tudor Period

The Reformation changed everything. Many pieces of ecclesiastical embroidery were destroyed, though some were quietly smuggled out of churches and repurposed for clothing and furnishings — which is how they survived at all.

Pattern books arrived from Europe, and embroidery shifted from the church to the home. Wealthy households filled their dark wood-panelled rooms with embroidered cushions, hangings, and table covers, mostly created by professional embroiderers.

The Elizabethan period (1558–1603) brought a burst of creativity. Silk, satin, and linen appeared with ornate gold and silver thread outlines. Designs featured freely drawn natural forms — pansies, roses, carnations, honeysuckle, fruits, animals, birds, and insects. Embroidery decorated everything from wall hangings and curtains to jackets, gloves, caps, and even mittens.

The Jacobean and Stuart Period

Jacobean embroidery (1603–1625) went big — literally. Designs were significantly larger than anything before, with huge sprays of flowers and many-branched trees rising from mounds of earth, with stags fleeing leopards through the foliage. The palette favoured light browns, light greens, orange, and peacock blue, likely limited by the natural dyes available.

The Stuart period saw a decline in design quality, but it also produced one of the most charming techniques in embroidery history: stumpwork (c. 1650–1690).

Stumpwork is raised embroidery — motifs padded with wool or horsehair to create little sculptures on the fabric surface. Whole landscapes featured castles, palaces, fountains, gardens, clouds, and radiating suns. Scale was cheerfully ignored: insects were stitched as large as animals, and humans were far too big to fit inside the castles they stood beside.

Many stumpwork pieces were made by young girls — some as young as eleven — who would stitch the panels and then send them to professionals to be mounted onto books or caskets. These pieces were treasured possessions, often stored inside an outer box to keep them clean, since the raised surfaces would have been almost impossible to dust.

New Influences and Revival

Early 18th-century work continued the trends of the previous century, but gradually the style became much more naturalistic. Embroidery began to imitate brushwork so closely that the stitching almost resembled painting.

Trade with China and the Far East introduced new design influences — exotic birds with spectacular plumage and flowers resembling lotus and chrysanthemum appeared alongside traditional English forms.

There was a notable shift from wool to silk, and a growing interest in embroidery for furniture. Chair and stool covers were worked in cross stitch, petit point, and gros point. Both men's and women's clothing featured finely embroidered sprigs, borders, flowers, and leaves, often with metal threads, using satin stitch or long and short stitch.

The 19th century was a period of revival rather than originality. The introduction of machinery and mass-produced braids and motifs changed the picture entirely, and as women's lives expanded beyond the home, there was less time for domestic needlework.

But one form thrived: the sampler. While samplers had existed for centuries, they became one of the chief occupations of the embroiderer in the 18th and 19th centuries. Typically worked in wool cross stitch on canvas, they followed a recognisable format — the alphabet, a quotation (often Biblical or a rather gloomy rhyme), formal motifs, and a border, with the stitcher's name, age, and date.

Historical Embroidery You Can Visit

Some of these treasures are still on display. If you ever get the chance, these two National Trust properties are well worth the trip.

Arlington Court, Devon

A stunning collection of historical needlework tucked away in a Regency house on the edge of Exmoor.

See the collection →Wallington, Northumberland

Beautiful embroidered furnishings and textiles in a grand house with centuries of stitching history.

See the collection →Into the Twentieth Century

The 20th century brought new materials, new techniques, and eventually a complete rethinking of what embroidery could be. But that's a story for another page.

What's worth noticing is the thread that runs through all of these periods: people have always wanted to make fabric more beautiful. The tools and materials change, the fashions come and go, but the impulse to pick up a needle and create something by hand? That hasn't changed in over a thousand years.

And every time you sit down to stitch, you're part of that story.

Continue Exploring

Blackwork Embroidery

The counted thread technique Catherine of Aragon brought to England.

Explore blackwork →Stumpwork Embroidery

Raised embroidery with castles, landscapes, and tiny 3D sculptures.

Explore stumpwork →Couching Stitch

The technique behind Opus Anglicanum — still a beginner favourite today.

Learn couching →Hand Embroidery Supplies

Everything you need to start your own chapter in embroidery history.

See supplies →History of Needlelace

How embroidery gave birth to an entirely new textile art form.

Read the story →

Stay connected between projects

If you’d like occasional updates from my embroidery room, including new patterns, gentle tips, and little things I think you might enjoy, you’re warmly invited to join the Stitchin’ Times newsletter.