- Home

- History of Embroidery

The history of embroidery in England

A site on needlework wouldn't be complete without looking into the fascinating history of embroidery.

As an embroiderer with over 50 years experience, I'm looking forward to sharing my passion for this ancient craft with you.

When I'm not stitching, you can find me exploring the majestic stately homes of England, where I love studying their exquisite needlework collections. In fact, I've written two reports about my visits, which you can access below, complete with photographs of the stunning pieces on display.

To add a personal touch to this article, I've included illustrations from an old exercise book created by Helen Whiteford, a talented schoolgirl in the 1930s.

These drawings not only showcase her artistic skills but also provide a glimpse into the past, when embroidery was taught at school.

Styles of embroidery through the ages

Part 1: Anglo Saxon | Norman | Medieval

Part 2: 16th C | 17th C | Jacobean | 18th C | 19th C

Embroidery is a beautiful and ancient art form that has been used for centuries when decorating fabric. The characteristics of British embroidery have altered over time, and there is no discernible style that has stayed consistent throughout the nation's history.

The emphasis was originally on ecclesiastical works, but in Elizabethan times, The Stuart period and the 18th Century the changing fashion trends meant richly decorated garments came to the forefront. Later came Masonic guilds which commissioned embroidery for their ceremonies.

In fact, the history of embroidery is deeply rooted in the domestication process. From threads to cloth, we've always been creating our own embroidered clothing and decorating household linens with extra flair - whether for a more formal or personal look!

The Anglo Saxon period

The early examples we have come across date back as far as Anglo Saxon churches which tells us this craft began before Christianity became prevalent throughout Europe - possibly even predating that religion altogether? Aldhelm Sherbourne, in a document on Ecclesiastical and Domestic work from about 700 AD, speaks highly about his countrymen's skills, saying "In those days no English artisan would touch needlework unless he had been trained".

The ancient kings of England, such as Edgar, were known to be generous towards the monks that dwelled within their realm. Chronicles tell of royal gifts given to the monks, such as richly-embroidered robes and vestments, used to create church ornaments.

The story of the Durham Embroideries is one that makes for intriguing history. These are works given by King Athelstan, in honor to Saint Cuthbert. Found in the Cathedral in the 19th Century, an inscription proves the date of creation to be around 1000 AD.

They comprise a stole and maniple (a fabric strip hanging from a priest's left arm) , embroidered in red, blue, green, purple and gold thread on a linen ground lined with silk. The design of the stole has the Holy Lamb with figures of the Apostles on each side. Not all the twelve figures remain intact.

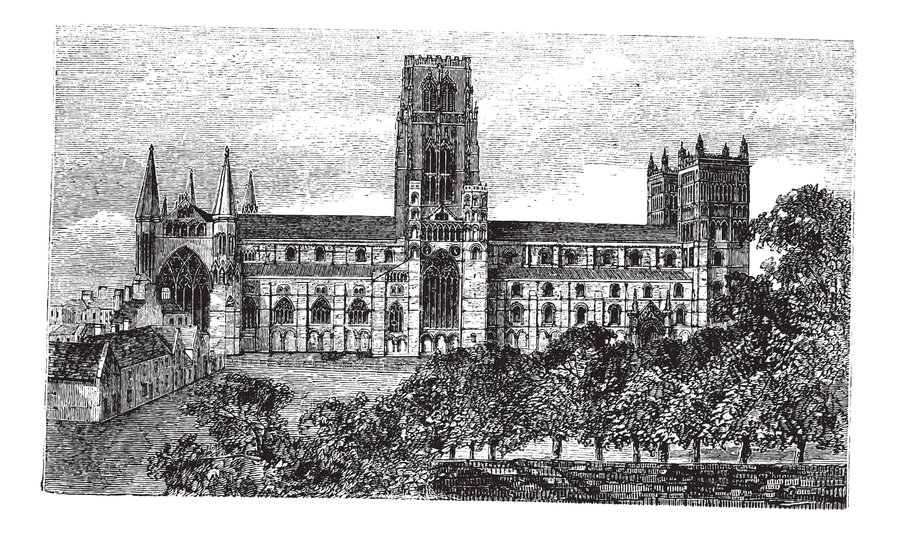

Durham Cathedral 1890s - Copyright: morphart

Durham Cathedral 1890s - Copyright: morphartThe Norman Period

Secular and ecclesiastical embroideries are records of great importance. They reflect the social conditions in which they were created, but also show us what life was like for those who lived centuries ago.

The Bayeux Tapestry, for example, shows scenes from the Norman Conquest with Latin inscriptions. It is said to have been commissioned by Bishop Odo, half brother to William the Conqueror, at the end of the 11th century. Evidence points to its creation, in England, within a few years after the time period depicted.

Although it was put on display after its construction, there is no further mention of the tapestry until it was included in an inventory of Bayeux Cathedral in 1476.

The historical importance of this treasure was not fully realized, resulting in it serving as a covering for an ox wagon on route to Paris during the Napoleonic Wars.

As many artworks were destroyed during the French Revolution this mundane use may have actually saved it!

How was the Bayeux Tapestry made?

The Bayeux Tapestry is a piece of hand embroidery rather than a woven tapestry. It is actually made up of several sections which may have been worked by different people, as there are many breaks and joins in the border.

A long strip of coarse linen, it is 230 ft long and 19 and a half inches deep. The last section of the border is incomplete, as are some other sections.

The images are full of life and energy, and the whole thing is a fascinating, lively depiction of historical events.

The figures are embroidered using two types of wool using the surface embroidery techniques of stem stitch and laid work, using two strands. Colours used include five shades of blue, two different greens, buff, red and grey. These colors are used with little regard for the true representation, for example there are blue and red legs on the same horse, and green hair on the figures.

The solidity of the laid work is even more pronounced when seen up close; it has a 3D quality to it that make the images leap out at you.

Every scene on the tapestry was drawn by hand before being embroidered, making this an immensely skilled piece of craftsmanship - despite its simple form, there are many subtle variations in body shape and posture among the different scenes. It is a treasure trove of information on architecture, fashion, and armour. In reality, it is the finest record we have from the time period.

The Latin inscriptions are beautifully drawn Roman lettering, clearly the product of an educated person.

A narrow 3.5 inch border at the top and bottom, running the whole length, is filled with all kinds of ornaments: birds, beasts, rural scenes and illustrations of Aesop's Fables. Here and there the border is broken into, by detail from the main scenes.

Embroidery in Medieval Times

This was the great period of English Hand Embroidery and the high standard of work made the country famous throughout the world.

The most obvious characteristics of the figure work are its artists' renditioning of faces with high foreheads and bearded men with shaven upper lips, although in some case hair and beards were worked in unnatural colours.

There is a sincerity and dignity in the figures, which is obvious in spite of the rather childish drawing and the absolute lack of perspective and proportion.

Details of birds, lions, and leopard heads along with foliage of vine, oak and ivy help to make up the designs.

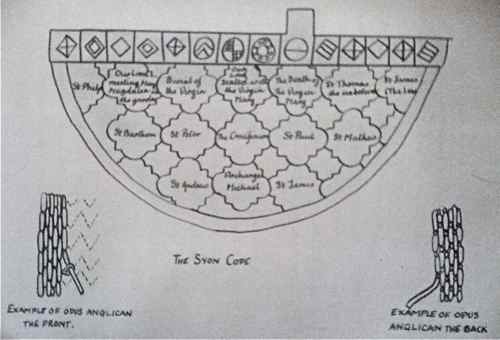

One of the special embroidery techniques of the period was known as Opus Anglicanum. It was a type of couching which had the appearance of satin stitch worked in a chevron pattern. On the back the linen threads are in parallel lines with the gold thread encircling them, see the diagrams on either side of the cope below.

The Syon Cope, (a type of ceremonial cloak) is a splendid example of Opus Anglicanum. In this piece of decorative embroidery, as in many other embroidered clothing of the time, the linen ground is entirely hidden by stitches in gold and coloured silk thread. The body of the cope is covered with interlacing quatrefoils outlined in gold, filled with scenes from Christ's life and those in veneration to him.

The ground of the quatrefoils is covered in red embroidery silk thread, with the intervening spaces in green, and is worked in underside couching in such a way that a chevron pattern is produced on the surface. The features and drapery of the figures are worked throughout in fine split stitch, characteristic of this type of work, and most suitable for accurate and delicate drawing with the needle. It dates from the latter half of the 13th century.

Another cope, The Tree of Jesse Cope, shows a figure of Jesse, lying on the ground, from whom springs a vine whose branches cover the whole ground of this cope and encircle the various figures. In the middle are David, Soloman and the Virgin with the Infant Saviour. Within the lateral branches are figures of the King and prophets, each holding a scroll inscribed with their names.

The cope had at some time cut into pieces, and parts of it used for other purposes, but has since been reassembled.

From the year 1718 to 1857-58 it was kept in the Roman Catholic Chapel at Brockhampton near Havant, Hampshire. It was afterwards in the possession of the Rev. F H Van Doorne at Corpus Christi House, Brixton Rise.

It was bought from him by the Victoria and Albert Museum, in London, a wonderful place to visit if you are interested in hand embroidery history along with other works of art.

A green orphrey, a strip of velvet with elaborate hand embroidery worn by priests, decorated with figures of angels and saints has been preserved with the fragments, but it evidently did not belong to the cope originally.

Another example of Opus Anglicanum work done around this time were the Catworth Cushions. These five small cushions, 23cm wide, also started life as part of an orphrey and were formerly housed in St Leonards Church, Catworth, Huntingdonshire. In 1902 they were sold to the V&A for the princely sum of £25, with the permission of the Bishop of the Diocese of Ely.

Worked in gold and silk threads on a silk ground that has faded to a pale brown, they depict figures of the apostles and saints beneath canopies. The shields of arms, belonging to the first Earl of Huntingdon, beneath some of the figures, help to date the work. It is assumed that the embroideries have some connection to the wedding of William de Clinton, the Earl, to Juliana de Leyburne, in 1329.

The decline of embroidery

The beginnings of the 15th century saw embroidery on a decline, with many signs that it had passed its prime. Signs of this decline during this time period included...

- The excellence in technical skill diminished with time and it became increasingly difficult to achieve fine-looking designs due to changes in design composition

- Faces were often crudely drawn as well - the figures didn't even look human anymore!

- The characteristic natural architectural details like angel's wings or vinework weren’t present at all, because they had been crowded out by ornate embellishments that weakened their beauty rather than adding anything special.

A revival!

Later in the history of embroidery there came a period of revival.

This new style was different from the earlier work. Velvet and satin were favourite ground materials and floral motifs such as the pomegranate, Tudor rose and fleur-de-lys embroidery patterns were used. These often had lines and spangles decorating them. The stitching was often a panel, superimposed on the richly decorated background of brocade.

As this page is getting rather long, so I will continue the history of embroidery on another page...taking us from the 16th century forward to the 19th.

Stay connected between projects

If you’d like occasional updates from my embroidery room, including new patterns, gentle tips, and little things I think you might enjoy, you’re warmly invited to join the Stitchin’ Times newsletter.

No pressure. Just a friendly note now and then to keep you inspired.