The history of needlelace

Liz Bartlett, author of Lace Villages, shares the history of needlelace. She provides an in-depth look into this fascinating form of lacemaking. Thank you Liz. The photographs are stunning!

An example of Punto in Aria (17th century) Bobbin and Needle Laces - Identification ad Care: Pat Earnshaw :pub B.T. Batsford 1983:ch1:p9.

🧵 Your Questions Answered

To understand the history of needlelace, it's important to note that without embroidery, there would be no lace. However, close examination of the techniques used by both embroiderers and lacemakers, prove the point without a shadow of a doubt.

There are two main branches of the textile form known as lace;

- One a single thread form relies on the use of an existing piece of material and (or) a small pillow to support the design.

- The other (the multi-thread form) relies on a pricked pattern, fastened to a larger pillow stuffed with a straw or other firm filling, and the use of bobbins which are simply bone or wooden handles used to weight the thread, and to permit the maneuvering of the threads without soiling them.

The second is perhaps the more familiar face of lacemaking and is more related to weaving than to embroidery, the resulting textile of this second method of production is known as bobbin lace.

It is to the first method of lace production known as needlelace, that I refer when I say that lace originated from the elaborate drawn thread work techniques prevalent in the 16th century.

An outline of the technique

An important part of the history of needlelace is understanding the technique involved.

A strong couching thread is couched down with small catch stitches over the design of choice. This is a wonderfully free technique which permits the stitcher to work elaborate flowing designs, with little in the way of technical restriction.

Once the design has been selected it is usually transferred by tracing it on to an strong and shiny backing material, such as proper architects tracing linen, (which I prefer because it allows the needle to pass through it when couching, without tearing). With the design tacked down on to a strong material such as linen or polycotton (preferably in a good contrasting colour such as green or navy blue, a couching thread can now be laid around the main outlines of the design.

Although couching is not the most interesting part of the process it is the most important, for once completed this couching thread becomes the support thread for the entire structure of the resulting lace.

Small catch stitches pass over the couching thread/threads, down through the shiny backing and through the material base or foundation. These will eventually be snipped away when the lace is completed, so that the needlelace can be released to form an independent textile...hence the name of one of the earliest and most elaborate forms of needlelace "Punto in Aria" which in translation means "stitches in the air".

🧵 Want More Information?

Stitches used throughout the history of needlelace

In the history of needlelace, various stitches have been used for the fillings.

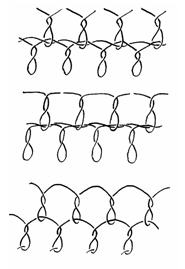

They are based on buttonhole stitch, but are given variety by placing them in a variety of groupings, some of which are shown below. This permits this type of embroidery to produce the combination of light and airy fillings interspersed by heavier closer work, that provides both the visual beauty and apparent fragility of lace to an embroidery form that is in actuality so structurally sound that examples of this lace form survive in better shape than its sister craft, bobbin lace.

The diagram shows a series of tulle stitches used to create net fillings in a variety of regional needlelace styles.

Historically although Hollie point is a form of needlelace thought to be unique to England, needlelace never really made it as a commercial enterprise here. Although large amounts of needlepoint lace were imported here, right up to and beyond the birth of our own bobbin lace industries in the late 16th century.

However unique varieties of applied needle embroidery indigenous to Ireland are a variation on the theme of needlepoint lace.

A huge and welcome revival in the making of Carickmacross (a combination of cut work and net embroidery) has taken place in recent years, and of course Youghall needlepoint with its unique floral style is very well known and flourishes alongside the net embroidery style of lace, known as Limerick Lace.

Below: an elaborate Youghall Needlelace collar (part of the authors collection) made as part of the trousseau for Lady Goodrich in the mid 19th century.

Stay connected between projects

If you’d like occasional updates from my embroidery room, including new patterns, gentle tips, and little things I think you might enjoy, you’re warmly invited to join the Stitchin’ Times newsletter.